Civic Science Observer

What is the case for and against a central repository for awarded grants in public engagement with science?

Public or civic engagement with science (PES) encompasses a diverse array of activities designed to strengthen the connections between scientific communities and the public. These activities include science communication, informal science education, participatory science, science journalism, and other initiatives that foster dialogue between scientists and local communities. As PES continues to grow around the world, so does the need for adequate funding to support these initiatives. However, the landscape of funding for PES is fragmented with the 150+ federal, philanthropic, and for-profit funding entities around the world using different terminology and platforms to manage and showcase what they are funding. The current landscape raises the question: Is there a need for a central repository to document information about awarded grants in PES by different funding organizations?

The case for a central repository

Proponents of a central repository would likely argue that it would bring much-needed structure to the fragmented funding landscape of PES. Currently, researchers, practitioners, and other stakeholders face significant challenges in navigating the diverse and disjointed sources of funding information, both for new funding requests and for what has been funded previously. A centralized platform could aggregate information about the grants funded each year across the different funding organizations, which would make it easier to search through the hundreds of PES grants that are awarded.

Such a repository would help groups identify underfunded areas, track trends across different themes, geographic regions, and target audiences, and align their projects more strategically with existing funding priorities. By making connections between awarded grants more visible, the repository could also reveal synergies between projects and foster collaboration among grantees. Additionally, the ability to track the scale, scope, and intended impact of funded projects could provide valuable insights for future funding decisions, ensuring a more strategic distribution of resources across the PES landscape.

Moreover, a centralized platform could enhance transparency and efficiency by standardizing the way funding information is categorized and presented. This would simplify the process of finding new funding opportunities, and also make it easier to compare and evaluate previously funded grants. Ultimately, such a platform could empower a wide range of stakeholders—from scholars and practitioners to policymakers and advocates—to make more informed decisions on the grants they write to support the growth and development of the PES landscape.

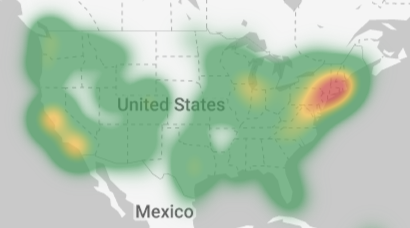

A centralized repository could also be further enhanced by integrating a dynamic dashboard that visualizes key areas of the funding landscape. Such a dashboard could allow users to filter and visualize information based on various criteria, such as geographic regions, funding amounts, project themes, and target audiences. Visualizations such as heat maps (Figure 1), trend lines, and network graphs could be employed to illustrate funding patterns, highlight gaps, and reveal emerging areas of focus.

The case against a central repository

Despite the potential benefits, there are several challenges to consider in creating a central repository for PES grants. Opponents would likely mention that the first major hurdle is the need for standardization of terminology and criteria across a wide variety of funding organizations. Each organization currently operates with its own set of definitions, data-sharing policies, and online platforms, making it difficult to achieve consistency and usability in a centralized platform.

Additionally, there is the complex issue of tracking and categorizing the impact of funded grants. Given the diverse goals, audiences, and approaches inherent in PES initiatives, developing a standardized framework for impact categorization will be challenging. While tracking intended goals and expected outcomes could provide a starting point, the complexity of comparing the impact of various grants would likely require significant resources and expertise. Coming to an agreement on the categories will not be easy.

Furthermore, maintaining and updating such a repository with new funding requests will require ongoing effort and commitment from all participating funding organizations. This will likely be a resource-intensive endeavor, especially given the need for continuous data integration and platform updates. There is also the potential resistance from some funding organizations that may prefer to maintain their existing platforms.

Finally, opponents would likely point to alternative solutions that could address many of the same needs without the challenges of building a fully centralized repository. For instance, enhancing existing databases with better categorization and standardized metadata may prove more feasible. The grant databases from National Science Foundation’s Advancing Informal STEM Learning (AISL) program, Sloan Foundation, and Wellcome Trust serve as potential models that could be emulated. These platforms support the idea of creating a network of regional repositories, where standardized data-sharing protocols could provide a decentralized yet collaborative approach to managing PES funding information. This approach offers many of the benefits of a centralized repository while maintaining the flexibility and responsiveness needed to address the local needs.

What stakeholders are saying

Adriana Bankston, a science policy expert and former CEO/Managing Publisher of the Journal of Science Policy and Governance, highlights that such a centralized platform would particularly benefit “early career trainees and faculty in navigating the types of PES projects they choose to submit their own grants on, but also increase awareness of what has previously been funded.” She mentions that ultimately, a central platform would aid early career researchers in navigating and building upon previously funded work, thereby reducing duplication of ideas and fostering collaborations.

However, she does agree that there are practical questions to consider when it comes to maintaining a centralized platform. For example, who will manage it, and where will the funding come from to support the platform? Additionally, she raises the issue of confidentiality of information that some grantees may prefer not to share.

Anagha Krishnan, an early career researcher and co-founder of Science Unlocked, notes that a centralized database would “streamline the process of matching grant bodies with applicants.” She explains that grant applicants, especially those from smaller or newer organizations, often struggle to find relevant PES funding opportunities and must rely on networks or word-of-mouth. A centralized PES repository, she argues, would make grant opportunities more accessible and “ensure that grant bodies and applicants are matched in the best way possible.”

Rose Leach, a biological anthropologist and science communicator, describes the creation of a central repository as an ambitious endeavor but “well worth the investment.” She believes that such a platform would enable groups to “more effectively collaborate and understand what has already been done in the space.” She points out that in the long run, this approach could lead to greater advances compared to continuing with decentralized repositories.

Peter Vollbrecht, Associate Professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at WMed and co-founder of Brain Explorers, states that “a central repository for awarded PES grants is a great idea, although one that I anticipate will be difficult to achieve.” However, he also emphasizes that the benefits of such a repository make it “worth pursuing,” particularly for early-career individuals who would be able to “see possible funding sources and funded grants in one place.”

Arianna Zuanazzi, scientist and former Symbiosis Director of Imagine Science Films, cautions that “practitioners bringing their sector-specific knowledge might feel overwhelmed and discouraged by the vast array and diversity of past grants and new funding opportunities.” She elaborates that any repository should “provide clear instructions on how to query, visualize, and utilize the available data (e.g., by utilizing dashboards, plots, or data query tools).”

Stephanie Castillo, a science communication researcher and video producer, points out that “deliberate categorization within a central repository would help expose blind spots or biases in funding, such as whether awards are disproportionately going to the same large named institutions/organizations or how diverse the awards pool is.” Castillo also highlights the potential of the repository to reveal gaps in the current landscape that could “guide PES researchers and practitioners to explore new areas or press funders to invest more in underfunded areas.”

So, which is it? Centralized or decentralized?

This is perhaps not the right question. Of course, the idea of creating a central repository for awarded grants in PES holds great promise. However, while the potential benefits are present, it is important to weigh these against the practical difficulties and consider all alternatives that could achieve similar goals with fewer obstacles and resources. The challenges associated with standardizing terminology, categorizing the funding, and maintaining a centralized platform are substantial and will require input from diverse groups. Ultimately, whether through a centralized repository or an improved network of interconnected platforms, the key lies in more engagement and collaboration among those providing PES grants and managing grant databases.

Additional Reading

2. The policy and funding landscape for public engagement. National Co-Ordinating Centre for Public Engagement.

Fanuel Muindi is a former neuroscientist turned civic science ethnographer. He is a professor of the practice in the Department of Communication Studies within the College of Arts, Media, and Design at Northeastern University, where he leads the Civic Science Media Lab. Dr. Muindi received his Bachelor’s degree in Biology and PhD in Organismal Biology from Morehouse College and Stanford University, respectively. He completed his postdoctoral training at MIT.

-

Audio Studio1 month ago

Audio Studio1 month ago“Reading it opened up a whole new world.” Kim Steele on building her company ‘Documentaries Don’t Work’

-

Civic Science Observer1 week ago

‘Science policy’ Google searches spiked in 2025. What does that mean?

-

Civic Science Observer1 month ago

Our developing civic science photojournalism experiment: Photos from 2025

-

Civic Science Observer1 month ago

Together again: Day 1 of the 2025 ASTC conference in black and white

Contact

Menu

Designed with WordPress