Civic Science Observer

Meet the duo behind AurorEye – citizen science effort that is capturing the aurora

Many of us have dreamed of seeing the northern lights, the aurora borealis, dancing in the night sky. For Vincent Ledvina and Jeremy Kuzub, this dream-turned-reality has taken them from one spectacle to another. As ‘aurora chasers’, Kuzub and Ledvina share a passion for making the beauty of this natural phenomenon more accessible to others. They’ve teamed up to develop and promote AurorEye — a custom-built user-friendly camera unit adapted to capture the aurora and help aurora chasers get involved in science projects. In this conversation, I talked with both Kuzub and Ledvina about their AurorEye journey.

Vincent, when did you first see the aurora? And how did that impact you?

VL: I saw the aurora for the first time when I was four years old. I grew up in the Twin Cities in Minnesota, and remembered seeing the aurora in the sky and thought — Wow! This is just amazing. That was back in 2003. There was this really big storm, a big space weather event called the Halloween storm. I was outside trick or treating and I remembered coming inside my parents’ house to count the candy and right as I was about to go to bed, I looked out the windows and saw the white lights, dancing around. I didn’t know what it was but my parents did. I think that experience really embedded in me this passion for the night sky, for science, and for the natural world.

How about you, Jeremy? What was your connection to the aurora?

JK: I grew up in Alberta, Canada where we would see the aurora often when camping or even in town. As digital cameras became more capable I also began traveling to photograph the aurora, in places like Yellowknife, Whitehorse, Iceland, and Norway. Although you can see them many times, they are different every night and vary by location and solar activity.

Vincent, you are a scientist studying the aurora. How would you describe an aurora to someone who has never seen it?

VL: Aurora is the perfect phenomenon that illustrates the connection between the Sun and the Earth. When you peel back the layers of the sun you can see that there’s a lot of activity there. It’s not just this static ball of light. It’s like a boiling cauldron of plasma with tons of ejections coming off the surface, into the sun’s atmosphere, and out into space.

The sun produces a stream of charged particles called the solar wind. I like to imagine it as a hot cup of coffee, and the coffee inside the mug is the sun, and the steam coming off the top is like the solar wind. It flows out from the Sun and throughout the solar system. And that solar wind has energy associated with it, in the form of charged particles and magnetic fields. Once in a while the solar wind can leak through the weak points of our magnetic poles, which are at the north and south geomagnetic poles. Like water flowing around a rock in a stream, it comes in contact with the Earth’s magnetic force field, the magnetosphere.

The magnetosphere shuffles these charged particles around like a game of pinball and eventually shifts the particles into the auroral ovals, a region of the geomagnetic field where the auroral phenomena occur.

How can one locate the aurora?

VL: I use an App called Aurorasaurus, which is a citizen science project by NASA that allows people to report on the location and time when they saw the aurora. So I had my first aurora chase with the help of Aurorasaurus.

Fast forward a few years, you went to college in North Dakota. Tell me what happened during that time that helped solidify your passion for aurora research.

VL: Going into college, I already knew what I wanted to do: a Bachelor’s of Science in Physics. Alaska was already on my horizon because I wanted to do aurora photography. I wanted to go to the University of Alaska, Fairbanks for undergrad, but my parents wouldn’t let me because it was too far! But, the University of North Dakota is very close to the Canadian border and close enough to some really dark skies. Even on nights when the geomagnetic activity is low or moderate, you might still see the aurora. So I was really excited about that.

I was able to take photos and post them on social media. I also created a YouTube channel on my aurora-chasing journey. And then in 2020, I met Dr. Elizabeth MacDonald, who founded Aurorasaurus, at an American Geophysical Union conference. I told her the story about how I used Aurorasaurus, and how I was passionate about aurora science, and about outreach and education. And she offered me an internship!

That sounded great! Through Aurorasaurus, you also met your colleague Jeremy Kuzub who developed the AurorEye. Can you tell me a bit about what AurorEye is?

VL: Yeah! So, it’s an all-sky camera with a fish-eye lens designed by Jeremy Kuzub, who is also the founder of AurorEye. I’m currently helping out with the beta testing. It’s made out of off-the-shelf equipment. The one I have has a Canon EOSM50 as the main camera component. Unlike a special science camera that can cost about $50,000, this one can be assembled for less than $2,000. It’s user-friendly. It is also portable. The cameras that scientists use are usually fixed in a location. So, if there are ever clouds, that camera is not going to be able to move out from underneath the clouds.

AurorEye also comes with a built-in Wi-Fi network, which is really nice, because you can maintain a live feed as you monitor things in the sky. It’s also “science-grade”. And I say science grade with quotations, because it’s not a science grade camera, but it has accurate GPS geo-locating capability and accurate timekeeping. And that’s really important because a lot of times in science, as we are looking at these all-sky images coming off of cameras, you’re also trying to correlate them with satellites moving over the field of view of the camera.

Aside from that, it’s also a great educational tool and a platform for observing aurora. I was out last night with a few undergraduate students to show them what can be done with the AuroraEye camera and how all sky images are used for scientific data collection.

Jeremy, as a computer scientist, what motivated you to create AurorEye?

JK: I wanted a camera that was fully hands-off and can capture the whole night sky automatically. When you are experiencing the aurora they can cover the whole sky and the motions are fast, moving from horizon to horizon in a few seconds when active. A camera with a conventional lens doesn’t get the whole picture, and I found I was working with the camera instead of enjoying the aurora.

At the same time, I wanted the camera to capture useful data that could synchronize with science instruments, like the camera and magnetometer and satellite networks that monitor aurora. I had a background in hardware and software, so I wanted to see if I could make a compact, portable all-sky camera that could provide all-sky imagery and timelapses, and be potentially useful scientifically.

Can you speak about the citizen science efforts with AurorEye? What sparked those initiatives and who/which scientists do you collaborate with on what kind of projects?

JK: AurorEye units have captured some interesting phenomena including “Quiet STEVE” which has been the subject of research by Dr. Bea Gallardo and a team of researchers.

Several units are currently deployed for citizen scientists across Canada and Alaska, who I met through the Aurorasaurus.org project led by Dr. Liz MacDonald.

We have also collaborated with Dr. Eelco Doorbos, a researcher at Koninklijk Nederlands Meteorologisch Instituut to integrate the timelapse video from AurorEye into his Space Weather Timeline Viewer web application, which allows us to replay the aurora imagery in synch with data from satellites, magnetometers, and other space weather data. This integration between instruments helps researchers understand the big picture, from solar activity to Earth’s magnetosphere, and the aurora.

What is special about AurorEye that makes scientists want to include it in their research?

JK: The portability of the camera makes it useful for fast-response situations.

For example, the camera is currently being tested as a support instrument for sounding rocket launches into the aurora, in order to document the aurora around the time of the launch. This was actually part of Vincent Ledvina’s PhD project.

In addition, the low cost, portability, and rapid deployment ability complement other scientific instrument networks and citizen science projects. There has been interest in making the cameras available for fast, dynamic, adaptive camera networks across more southern latitudes during the current Solar Maximum. These capabilities will allow scientists to capture phenomena during strong geomagnetic storms that would otherwise be too far south for some of the other aurora imaging networks.

And then of course, the AurorEye cameras are useful for citizen science collaborations with researchers. There has been interest from planetariums to use the high resolution timelapses in their projection domes. We have made an 8-minute show of the best moments from the 2024 season that has been distributed as educational media.

The network of people and opportunities has grown from when we first started a few years ago. I have a website about the AurorEye camera now and a Youtube channel for timelapse movies: AurorEye.ca

How about you, Vincent, what do you do now?

VL: I’m now a second year space physics PhD student at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. I’m also an intern at the Aerospace Corporation, so I’ll be going into my third summer with them in 2025. I study the aurora, particularly auroral beads, and also do a lot of work with citizen scientists through AurorEye to encourage aurora chasers to get involved in research.

Jeremy, what have you learned so far about the development of AurorEye?

JK: I have learned that there is an amazing community around aurora citizen science. The people make it happen. I am always excited to see what the operators have captured and see their time lapses. The research community has also been collaborative and helpful.

What do you hope to be the next step for AurorEye?

JK: At the moment the AurorEye cameras are self-funded and distributed to aurora chaser citizen scientists who are in locations where they frequently see and photograph the aurora.

We have now completed version 2 of the AurorEye which incorporates lessons learned about hardware, software, and manufacturability.

If there is institutional interest we could look at collaborations to build several units to deploy across a large geographic region as a fast-response network.

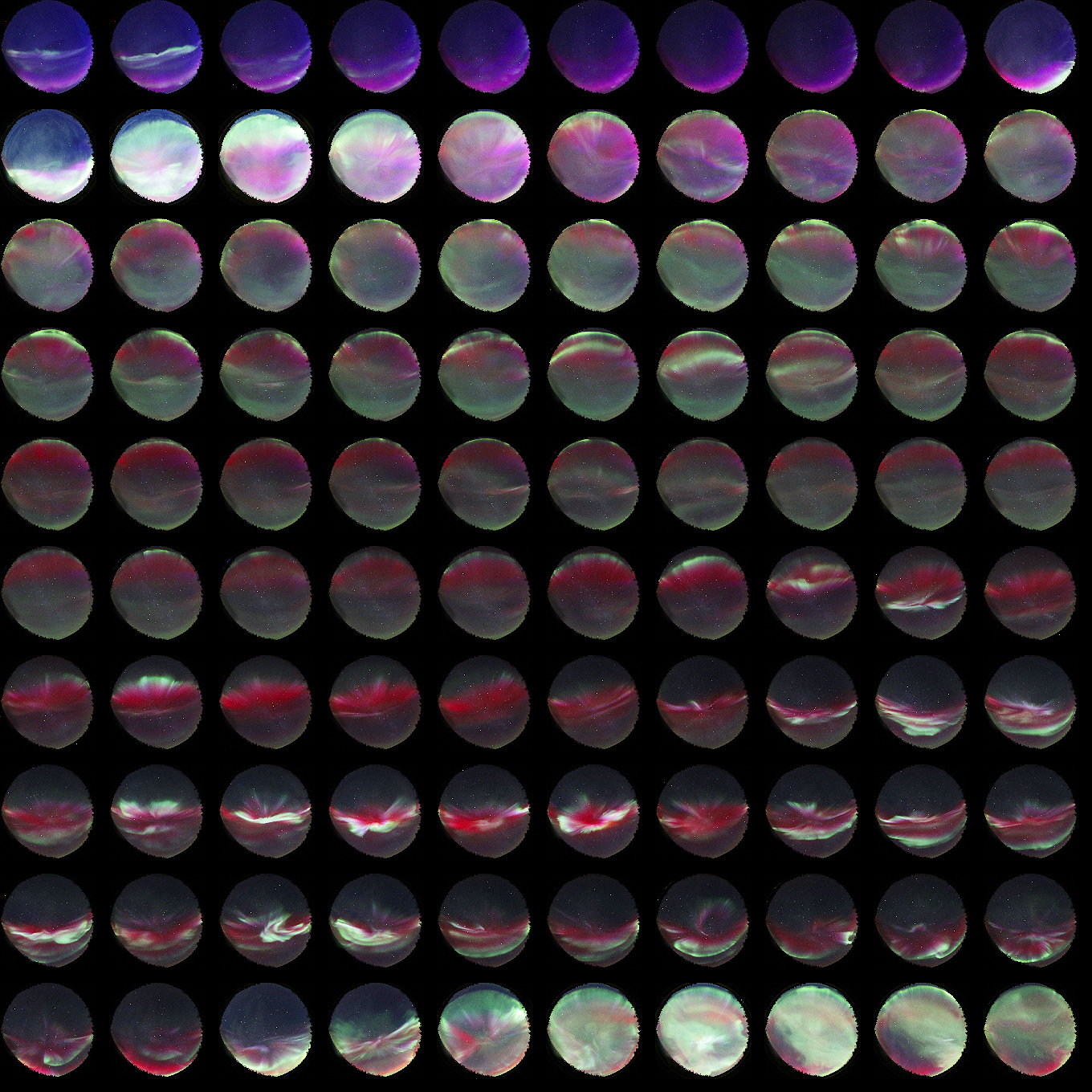

Examples of AurorEye timelapse:

-

Civic Science Observer1 month ago

What are the objectives of the Neurotech Justice Accelerator at Mass General Brigham?

-

Civic Science Observer1 week ago

Meet the New Hampshire organization changing the way we see insects

-

Civic Science Observer2 months ago

Dear Colleagues: Now is the time to scale up public engagement with science

-

Civic Science Observer2 weeks ago

Dear Colleagues: Help us understand the national impacts of federal science funding cuts on early career researchers in academic laboratories