Civic Science Observer

How the Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont is navigating the tensions around citizen science

Sometimes, when a research organization has an active and robust public outreach component, it creates a tension between providing educational programming and offering the public with opportunities to conduct citizen science (also called participatory science).

This is an issue that the Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont, a research and environmental education center in Townsend, Tennessee, has grappled with, according to John DiDiego, Tremont’s education director.

“We’ve gone back and forth and realized that there were times when we used citizen science projects to engage people with scientific learning, but we realized that the project wasn’t even a good fit” for citizen science, DiDiego told Civic Science Times. “What we wanted was more of a softer science approach, where a person could do an entire science process. However, it wasn’t contributing to any citizen science. It wasn’t contributing to research anywhere.”

Now, to navigate this problem and determine whether a project should have a citizen science component, instead of just an educational one, Tremont weighs several factors including the intended audience, time and staffing resources, and funding availability.

As a small nonprofit, it’s important to consider project funding. Each project has to balance serving the public with opportunities to engage with science, while still ensuring there is enough funding to provide those opportunities, DiDiego said.

“We used to call it all citizen science. There was a time when we just called everything that. But we reached a certain point where we realized this isn’t citizen science anymore,” DiDiego said. He adds, “This is science learning, and it’s interesting, and it’s a very good process. But it’s not addressing any research problem. It’s not actually contributing data.”

“So, we’ve had to be more specific in the way we use our language, knowing that both processes might be valid for the outcomes we want. But we don’t call everything ‘citizen science’.”

Citizen science is a smaller component of Tremont’s programming, according to DiDiego. Yet it is an integral one as it provides an opportunity for volunteers and visitors to experience ongoing, substantial research on the flora and fauna of the Smokies.

Some of Tremont’s popular projects include the bird banding program, in which volunteers work with staff to monitor the breeding bird population in Walker Valley, as well as the monarch butterfly education program, which tags butterflies and offers the public a taste of Tremont’s research monitoring butterflies’ migration habits.

All Tremont’s projects take place on the grounds of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park or in the immediate vicinity. Tremont works with the National Park Service and its park naturalists and researchers.

Other citizen science projects include a pond breeding amphibian project where volunteers go out in the winter to wetlands in the park and look for the presence and development of wood frog eggs and spotted salamander eggs. Another project is the amphibian road survey project, in which one of Tremont’s teacher naturalists walks with volunteers to look for amphibians and reptiles crossing area roads. There are also projects on phenology and soil respiration.

One longstanding citizen science project has been monitoring the salamander population in local streams, because, according to Tremont’s website, “the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is known as the ‘Salamander Capital of the World,’ with higher diversity of salamanders than anywhere else of similar size.”

As Tremont continues its work on these projects, another problem that DiDiego has come across is whether an optimal volunteer experience takes place over an extended length of time or whether shorter glimpses into one stage of a project is sufficient enough.

“We’ve had to wrestle with the challenge of a whole project like the salamander project. There are protocols for collecting the salamanders and extracting them from the water, measuring the salamanders — weighing, identifying, and making note of all that. And it takes a long time,” DiDiego said. “We could involve the students in one part of that — maybe just the collecting — and then we go off to the side and do all the other measurements and whatnot. But what is the value of a person seeing just one aspect of the whole project versus doing a whole project?”

The value of volunteers

Despite the challenges, DiDiego and Tyler Thomas, manager of science literacy and research at Tremont, say they have been humbled by working with the volunteers, especially the long-term ones who have dedicated themselves to monitoring the same stream for salamanders for years.

“We have long-term volunteers who are invested and are an incredible resource, even for my onboarding and getting up to speed on these things,” said Thomas, who started working at Tremont in March. “I’ve spent a lot of time going out with the volunteers who have been doing these projects for 10, 15 years. They know every tree or every rock. I’ve learned a ton from them.”

Long-term volunteers have also served as guides to newer volunteers by helping them navigate through project protocols, such as how to turn over rocks safely when conducting salamander monitoring.

Having citizen science volunteers provides “different layers of usefulness,” said DiDiego.

At one level, Tremont can facilitate learning experiences for teachers, who can then take what they’ve learned at Tremont to the classroom.

At another level, the volunteers benefit Tremont by elevating researchers’ confidence in communicating their scientific work to diverse audiences and through different mediums, such as graphics and other visuals. The National Park Service also benefits from the volunteers’ persistent data collection efforts.

“I’ve just been impressed by how much data can be collected by volunteers,” Thomas said. “It’s just cool how much science can be done by folks who, whether they have science backgrounds or not, have just been interested in helping out.”

And at another level, having citizen science volunteers may benefit the individual.

“At a certain point, we realized that for some of the projects, we can get volunteers who will sign up to do them on their own. They’ll just come out month after month with a group of family or friends and do this monitoring,” DiDiego said. “Even though they weren’t paying us and we weren’t paying them to do any of this stuff, they were having this deep experience of a place and of a species. It was a hugely impactful and deep experience for them to monitor that same creek over and over.”

Realizing the impact of volunteers’ experiences “transformed what we thought about who our audience is and where our impact extends to. It made us open up our eyes to see these projects as something other than just collecting this information and reporting it out. It’s about a really deep, deep educational experience in itself.”

Joanna Marsh is a freelance writer and journalist based in Washington, D.C. For The Civic Science Observer, she reports on new developments across the citizen science landscape, covering both new research and on-the-ground practice. Her work highlights how local communities are engaging with scientists to contribute to ongoing scientific research and lessons being learned by the involved stakeholders.

-

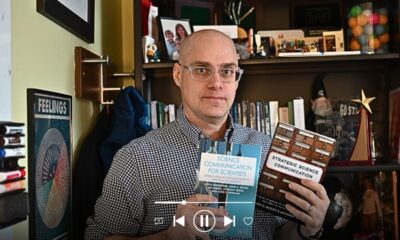

Audio Studio1 month ago

Audio Studio1 month ago“Reading it opened up a whole new world.” Kim Steele on building her company ‘Documentaries Don’t Work’

-

Civic Science Observer1 week ago

‘Science policy’ Google searches spiked in 2025. What does that mean?

-

Civic Science Observer1 month ago

Our developing civic science photojournalism experiment: Photos from 2025

-

Civic Science Observer1 month ago

Together again: Day 1 of the 2025 ASTC conference in black and white

Contact

Menu

Designed with WordPress