Civic Science Observer

Boston resident Kwasi Agbleke is working to expand access to biomedical research in Ghana and across Africa

Kwasi Agbleke Ph.D. is the Founder and President of the Sena Institute of Technology (SIT), a private nonprofit research institute in Penyi, Ghana. Based in Boston, Kwasi travels frequently to Ghana to lead SIT’s initiatives. Dedicated to developing new technologies and expanding access to biomedical research across the African continent, SIT’s work includes hands-on training programs, international fellow exchanges, conferences and seminars, and resource development. I caught up with Kwasi at the Saloniki Greek restaurant in Harvard Square, Cambridge to discuss the ongoing progress at SIT and his vision for the future. Here is the transcript of my conversation with him that’s been edited for clarity.

Fanuel: Kwasi, welcome back.

Kwasi: Thank you.

Fanuel: So, give us an update from the last time we chatted. SIT was on fire with a lot going on. Is it still on fire?

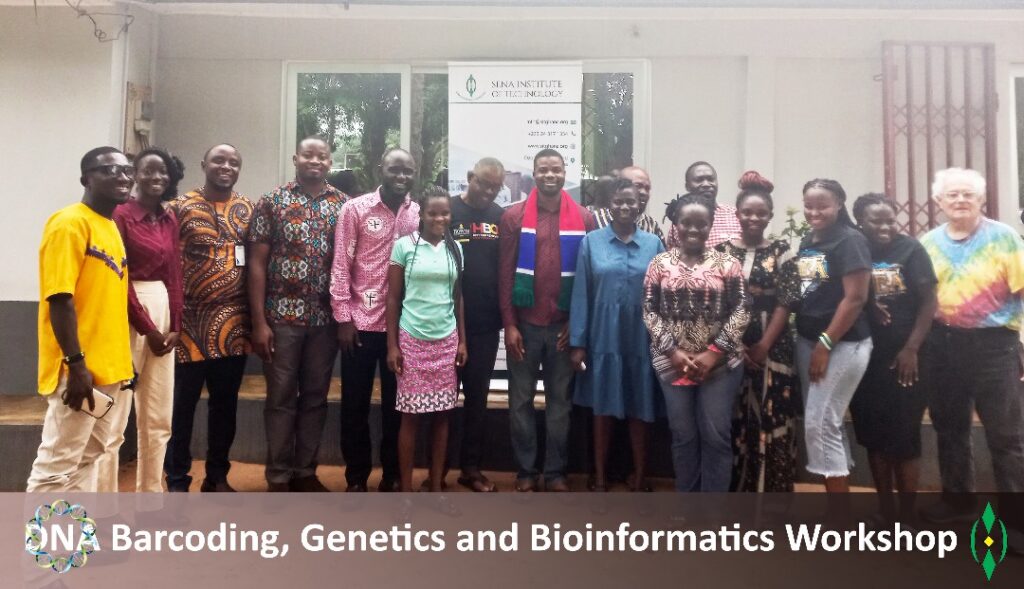

Kwasi: Yes, it is still on fire. The last time we talked, I think that was right after we finished our conference. It was wintertime, actually. So, we had completed the conference in Ghana, did the DNA barcoding workshop, and since then, a lot has changed in how we engage the community.

Fanuel: Give us some examples.

Kwasi: Sure, I’ll give a few examples. One is that we’ve started several partnerships with universities in Ghana to train high school and college students.

Fanuel: So they come directly to your campus?

Kwasi: Yes, they come to the campus. We give them a minimum of one month where they stay at the institute. We train them on practical research and hands-on experience. These programs have now taken root, and we have a system in place. Secondly, we’re also looking at tertiary institutions—the lecturers, the people training students. We need to work with them to upskill what they can do. So, we’ve started a program where we organize practical, hands-on experiences either at the institute or off-site, where we invite them to participate.

Fanuel: This sounds like a very busy place. How do you fit everyone on campus?

Kwasi: It’s a small campus, so we usually make a call or put out an ad that says, “We’re organizing this program,” and we take the top ten applicants. For our last program, we had about 145 applicants and ended up taking only 15.

Fanuel: Which program was this?

Kwasi: This was for DNA barcoding. We were training lecturers and high school teachers on how to extract DNA from plant materials and sequence it on-site to give them that sequencing experience. There was a lot of interest, but as you mentioned, our campus is small. So, we organized this program at the British Council in Ghana, used their space, brought everything from our institute—about three hours away—into Accra, and did the training on-site.

Fanuel: Wow, that sounds like it was both fun and maybe not so much fun?

Kwasi: Yeah, the fun part is seeing the experiment being done and finished. The not-so-fun part is carrying everything from the institute and worrying you might forget something. It hangs over your head until the program is over. Ideally, we’d love to have everything in one place at the institute.

Fanuel: I’m curious—have you received interest from others in the community? You went to the British Council, so have others asked if you could do similar events at their facilities or local communities?

Kwasi: Yes, we’ve had several universities asking if we can come to their campuses to host events. We’re working on a model for that. Right now, we’ve created several kits, or ice chests, that we call “lab in a chest.” Each chest carries everything needed, like PCR machines and electrophoresis equipment, all organized so that we don’t leave anything behind.

Fanuel: So, it modularizes the whole process. You have this package you could deliver to a university or a local high school, right?

Kwasi: Exactly. The idea is that whoever invites us can have us walk into their institution and do the training without worrying about missing something. High schools have also reached out, but it’s a lot of work. We have to balance training with our core mission of research, and our team is small. So, we’re pacing ourselves. For example, in two weeks, we’re training health professionals—lab technicians and diagnostic personnel—in molecular biology. This is a new area we’re exploring. Historically, we focused on academic institutions, but now we’re moving into professional institutions to provide training beyond their current skills.

Fanuel: You mentioned molecular biology, which covers a range of skills. What’s the main skill you’re training them in?

Kwasi: At SIT, the focus is on genetics. We train them in DNA extraction, sequencing, and testing. Another area is microscopy, where they can examine live or dead protozoa, like the plasmodium protozoa that causes malaria. Our modules cover DNA extraction, sequencing, running gels, PCR, and microscopy—preparing slides and specimens. These skills help them improve lab and healthcare services.

Fanuel: So you’re going to them for training. Ideally, they’d come to you, but you’re also providing access by going to them. Earlier, you mentioned capacity. It sounds like high schools are reaching out and professional organizations, too. How are you managing capacity for this demand?

Kwasi: Capacity is a challenge. We need to recruit people, train them with the right skill sets, and then have them train others. For example, we’ve organized workshops where previous participants become facilitators. It’s amazing to see their excitement and energy—they attended a program, and now they’re mentoring others. We have a small, well-trained team that can train others. With so many requests, though, we’re looking to avoid becoming solely an outreach organization. We also need to focus on research, data collection, and analysis. So, we’re planning to grow the team under two main divisions—one for training and one for research—so each unit can focus on its mission.

Fanuel: It sounds like there’s a high demand for this training and outreach. You can’t ignore it, but SIT’s foundation is research. Is there a balancing act, or even a tug-of-war?

Kwasi: Not quite a tug-of-war. We balance it by setting specific times for training, like summer, when we have an international exchange program. We bring in international students and engage local students in the same program. Summer has been the training season. If adjustments are needed, we pause research, deliver training, and then return to research. This system has worked well so far, but with growing demand, we may need a dedicated unit for education and training to handle logistics and make a timetable for training sessions.

Fanuel: Part of your outreach includes a YouTube channel, and you’re active on X/Twitter, for example. Especially on YouTube, you now have videos of some training sessions. What’s the goal there, and who’s the target audience?

Kwasi: We’ve kept our content basic, removed a lot of scientific jargon, and made it accessible for the general public. The audience is mainly young kids, high school students, and undergraduates who can see their peers doing this level of science.

Fanuel: Do you envision students doing these experiments at home, or is it more for them to see science in action?

Kwasi: It’s mostly to show them science in action and to encourage them to come to the institute for training. Running an experiment like this costs around $5,000 on average, which isn’t affordable for most students in Ghana. But seeing their peers accomplish these experiments gives them the motivation to reach out and join the next program.

Fanuel: Have you thought about live streaming experiments to local classrooms?

Kwasi: We tried that with university lecturers. During DNA sequencing, instead of having 30 people crowded around, we projected the bench onto a screen so everyone could watch without needing to be right there. It was engaging, and I agree it could be scaled up to multiple schools or institutions. My only concern is internet accessibility, but if there’s a central hub, students can gather to watch a live broadcast. We could go to the institution, set up the system, and they could watch everything.

Fanuel: Yes, a central hub could help overcome the internet barrier. If students could go to a local hub, they wouldn’t all need internet at home, and they could still watch you do experiments live.

Kwasi: Absolutely. And afterward, students could ask questions, with a facilitator on-site to explain things.

Fanuel: It sounds like we’re designing something in real-time here!

Kwasi: I think so. I can imagine students watching experiments in real-time with someone explaining each step. It could be a great learning experience.

Fanuel: If you end up doing this, we definitely want to hear about it. I want to finish with a question about the future. Last time, I asked about the future of SIT. Where is the future now?

Kwasi: As you can see, we’re always innovating in how we think about SIT. The future is as chaotic as the present. We keep changing our models. But the exciting thing is, the more we learn and the more we do as scientists, the more we refine our hypotheses. We come back to the bench, do the experiments, see what works, what doesn’t, and keep refining. The future of SIT is still chaotic, but in a good way. Think of it as positive entropy—there’s uncertainty, but it’s essential for making things work.

Fanuel: Exactly, it’s about finding clarity through uncertainty. We’ll keep this conversation going to track the growth at SIT. Thanks for talking with me.

Fanuel Muindi is a former neuroscientist turned civic science ethnographer. He is a professor of the practice in the Department of Communication Studies within the College of Arts, Media, and Design at Northeastern University, where he leads the Civic Science Media Lab. Dr. Muindi received his Bachelor’s degree in Biology and PhD in Organismal Biology from Morehouse College and Stanford University, respectively. He completed his postdoctoral training at MIT.

-

Audio Studio1 month ago

Audio Studio1 month ago“Reading it opened up a whole new world.” Kim Steele on building her company ‘Documentaries Don’t Work’

-

Civic Science Observer1 week ago

‘Science policy’ Google searches spiked in 2025. What does that mean?

-

Civic Science Observer1 month ago

Our developing civic science photojournalism experiment: Photos from 2025

-

Civic Science Observer1 month ago

Together again: Day 1 of the 2025 ASTC conference in black and white

Contact

Menu

Designed with WordPress